A former Somali refugee intent on bringing books and education to his compatriots languishing in sprawling camps in Kenya was on Tuesday named the winner of the UN refugee agency’s prestigious Nansen Award.

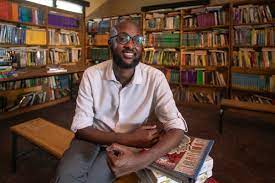

Abdullahi Mire, 36, was hailed for championing the right to education by putting 100,000 books in the hands of children in Kenya’s crowded Dadaab refugee camps.

“A book can change someone’s future,” Mire told AFP in an interview.

“I want every child who is displaced to get the opportunity of education.”

Announcing the prize, United Nations refugee chief Filippo Grandi described Mire in a statement as “living proof that transformative ideas can spring from within displaced communities”.

Mire was born in Somalia, but amid unrest there his family fled to Kenya when he was a young child.

He spent 23 years in Dadaab — a sprawling complex of three camps that were initially built in the 1990s to host some 90,000 refugees, but which today are home to around 370,000, according to UN figures.

Against what the UNHCR described as “monumental odds”, Mire not only completed his primary and secondary education in the camp, but managed to go on to complete a degree in journalism and public relations.

“My case is rare, and that inspires me to give back,” he said.

Mire, who on occasion has worked for AFP, was resettled to Norway around a decade ago, but while he liked living there, he soon decided to return to Kenya.

“Europe is nice and safe, but it depends what you want in life,” he said over the phone from Nairobi.

“There was something telling me that I could have an impact here, more than in Oslo.”

Back in Kenya, he was working as a journalist and reporting a story in Dadaab one day when a girl named Hodan Bashir Ali approached him and asked if he could help find her a biology book.

She wanted to be a doctor, she said, but at her school 15 students had to share a single text book.

“That was the start of my calling,” Mire said, adding that he bought the book for Hodan, who is now a registered nurse and still aspiring to become a doctor.

“That book opened a door for Hodan,” he said. “She is inspiring.”

Mire decided to set up the Refugee Youth Education Hub, raising awareness about refugees’ educational needs and seeking book donations.

To date, the refugee-led organisation has brought 100,000 books into the camps, and has opened three libraries.

“When you read a book, it is like you are travelling the world,” Mire said.

And for people traumatised by the conflict and wars they have fled, “books are the best way to heal”.

The programme has already boosted enrolment in higher education among the refugees.

“I know dozens of girls who wanted to be teachers who are teachers now,” Mire said.

“Books are about giving the opportunity to dream and to think about a career, about how to be a better citizen of this world.”

The Nansen prize, awarded annually, is named for Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who served as the first high commissioner for refugees for the League of Nations — the precursor of the United Nations.

The award winner receives a commemorative medal and a monetary prize of $100,000, to be reinvested in humanitarian initiatives.

Last year’s award went to former German chancellor Angela Merkel, who was hailed for the dedication she showed while in office to protect people displaced by conflict.

Mire, who will receive his award at a ceremony in Geneva on December 13, said the prize was “a huge honour for all refugee-led organisations”.

“I am not a philanthropist, I am not a rich person… but I believe anyone can make a difference,” he said.

“You don’t need to be a politician or a celebrity or a tycoon to have an impact. Everyone can have a role to play to make people’s lives better.”